Article written following my interview with Hind in Belgium.

The article’s sources are in French, but most websites offer an English translation or you can use a translator.

Hind had her veil removed against her will by illegal smugglers. Her mother was violently beaten and pushed to the ground by the Moroccan authorities at the Melilla border separating Morocco and Spain. These brutal and traumatic events experienced by Hind and her mother are unfortunately a reality. Each year, thousands of migrants cross the Spanish Moroccan border with the aim of reaching Europe.

A difficult crossing and a horror scene at the border

Hind is a young woman aged of 22 (at the time of her testimony) born in 2001 in the United Arab Emirates. She grew up there with her parents of Palestinian origin, her two younger sisters and her younger brother, who are now 19, 14 and 18 years old.

On 10 September 2018, aged 16 at the time, Hind and her family (mother, siblings, aunt, cousins and grandfather) left the United Arab Emirates. They were hoping for a better life in Europe, as they had always been discriminated because of their foreign origin. ‘The government refused to give us the nationality,’ she tells me. In fact, according to the young adult, most Emiratis socially exclude immigrants in their territory.

That same day, the family got on a plane and landed in a country that was not going to require them to spend a lot of money, given their lack of money to fly directly to Europe.

The country in question is Morocco. Located in North Africa, it is known to be one of the busiest crossing points for sub-Saharan migrants trying to reach the European Union. In 2023, 87,000 transit migrants were intercepted by the Moroccan authorities, according to the InfoMigrants information website.

As soon as they arrived on Moroccan soil, the family obtained a visa that allowed them to stay for almost a month. During those long weeks, they stayed in a small hotel for migrants. ‘I was in a small room with my mother, my sisters, my brother and my grandfather. There was also my aunt and her children. They joined us because they also wanted to change their lives. We were squeezed in all the time, it was difficult and unbearable’, Hind tells me.

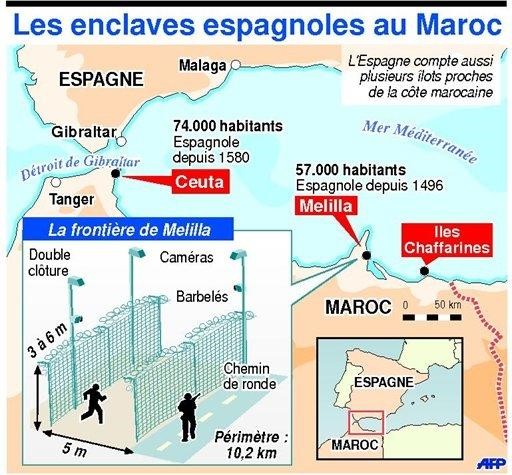

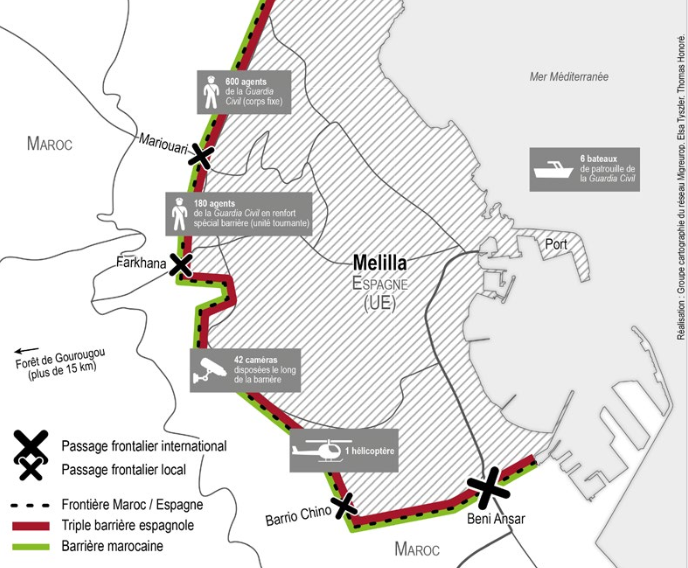

Morocco shares distinct borders with the enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla, which are also considered to be autonomous Spanish cities. They are in the north-west of the African continent. At the same time, Melilla serves as an outpost for Spain, surrounded by four fences with barbed wire and a deep trench. One of the fences acting as a land border with the Spanish zone is 9.6 kilometres long and 6 metres high, which can make it difficult to cross.

The Moroccan authorities are responsible for guarding it. Several times a day, large numbers of migrants attempt to cross it to have a chance of seeking asylum in Europe. Yet it is one of the most dangerous and deadly crossings in Africa. In 2022, UN experts estimate that at least 37 people died trying to scale the wire fences, as reported in the Human Rights Watch article.

Hind was one of the illegal migrants who made repeated attempts to cross the border at Melilla: ‘The Moroccan police were everywhere, there were large fences and a lot of agitated migrants jostling each other. Sometimes it was as if they were crammed together.’

She witnessed horrific scenes: ‘The migrants were pushed and beaten with truncheons and sticks, and there was blood all over the floor.’ Her mother was also a victim of the terrible treatment meted out by the members of this police: ‘They pushed my mother so hard that she fell to the ground with her belongings, which were all scattered around.’

During their last attempt to cross on 9 October 2018, her grandfather met some illegal smugglers and paid them to help them cross. ‘They would take 3 of us in the family each time in a car, then they would drop us off at the Beni Ansar border post hidden from the authorities. We only had to walk a few metres to get back to Melilla’, says the young woman.

Hind was not physically abused by the Moroccan police, but she had to remove her veil by force to cross: ‘The smugglers gave me a stolen identity card of an unknown Spanish woman, and she wasn’t wearing a veil in the photo. So, they forced me to remove mine to look as much like her as possible, otherwise they wouldn’t let me pass.’

Many irregular migrants pay smugglers illegally to get to the Spanish side of the border. For them, this is their only chance to leave Moroccan territory and escape the police. Hind says: ‘The police wouldn’t let you in if you didn’t have papers, they wouldn’t give you a chance. And if you failed to pass, they would send you back to where you came from.’ It is very common for the authorities concerned to send migrants straight back to their point and/or country of origin. These push-backs (the action of sending a migrant back without giving him or her the opportunity to apply for asylum on the other side of the border) are illegal, and the migrant’s situation is not considered even though his or her life may be in danger.

After managing to reach Melilla, Hind and her family were given asylum and were able to stay legally in the Spanish city. They lived for a month in an unsanitary centre for migrants. ‘The place was dirty, there was no hygiene. I had to share the toilets with men, because they were mixed. The food in the canteen was disgusting, and we had no money to buy anything else’, she says with disgust.

Unable to bear this life, the family left Melilla and took a boat to Málaga. They were then welcomed for three days in Madrid and hesitated to settle there definitively. But it didn’t happen, because the Spanish government only gave them six months to adapt and integrate by finding accommodation, learning the language and getting a job. A period that was far too short. As a result, the family left Spain for Belgium, travelling by FlixBus (a low-cost bus company), because they had distant relatives in Antwerp ready to receive them.

Today, despite the traumas of the past, Hind is a young student in Belgium where she lives with her family. They will never forget what they went through and will be scarred for life. ‘Some migrants have managed to enter Europe with arms and legs broken by the Moroccan border police,’ she concludes.

A look at conditions for migrants in France and in Europe

The problems associated with irregular migration affect both Western and developing countries, particularly in Africa. Numerous political decisions, such as agreements between states and laws, attempt to regulate these situations, causing controversies and, unfortunately, tragedies.

Vincent Latour is a lecturer and researcher at the Jean-Jaurès University in Toulouse. He has worked on migration and immigration policies in France, the UK and Europe in general. His expertise and his various research projects provide a better understanding of how certain European countries view migration.

According to him, the European Union takes a much more restrictive approach to migrants than it did a few decades ago. For example, from 1980 onwards, France began to strongly legislate in this field. ‘The subject has become highly political’, he says. France’s immigration law is a clear illustration of this. Its aim is to reinforce controls on undocumented workers in ‘métiers en tension‘ (unrewarding and badly paid jobs where job supply is higher than demand), to expel legal foreign nationals from the country if they are suspected of undermining public order, to make them sign a contract to respect republican principles and much more. All these measures clearly reflect the toughening of the laws on the topic.

However, this was not always the case. Between 1945 and 1970 (during ‘Les Trente Glorieuses’: the 30 years of post-war economic growth), European countries, including France, experienced massive immigration to serve their economic interests. ‘We used the term ‘migrant workers’ and let them come, without anticipating that they would settle down for the long term and reunite families. Now governments see this as a problem’, explains the teacher-researcher.

For this reason, many countries such as Spain and Morocco are establishing joint agreements to control their borders, with the help of the European Union. The Spanish authorities then call on the Moroccan security forces to evacuate people to their territory. As Hind‘s testimony shows, the evacuees were sometimes subjected to violence. At the end, the Spanish authorities deny any responsibility, and that is when the real problem arises.

In his article ‘Grande-Bretagne : une attractivité paradoxale’ (The United Kingdom: a paradoxical attraction), co-written with Catherine Puzzo and published in 2016, Vincent Latour examines the reasons why Great Britain continues to attract large numbers of migrants despite its insularity. These include the significant number of job offers and the important support provided by organisations such as associations/ voluntary organisations.

This is illustrated by the role of Simon. He is a final-year History & Civilisations Masters student in Toulouse (at the time of the interview) and a (former) volunteer with Utopia 56, an association that helps undocumented migrants and refugees. Every Tuesday, he takes part in the missions by distributing food and hygiene products. He also assists them with administrative procedures such as the ‘Aide Médicale d’État (AME)’ (State Medical Aid) and domiciliation.

Thanks to his involvement in events and information days, Simon can forge links with migrants, but it is often complicated to establish a real relationship because of the language barrier. ‘For example, the association pays € 20,000 a year for a translator via an application,’ he tells me.

Migrants survive. They have difficulty integrating because of the language and the mistrust they have of people in their host country. Most of them have left everything they had behind to come to Europe and have had traumatic experiences during their crossing. Therefore, the associations are doubling their efforts to integrate them, because they represent their interests. ‘The state gives them very few rights and duties’, he says with sorrow.

Key point

It is important to note that there are several types of migrants who leave their town and/or country of origin for various reasons. In Hind‘s case, it was for a more decent life. Moreover, I used the term ‘illegal migrants’ because she and her family were forced to be illegal to have a chance of entering Europe. This irregularity was only temporary, as the protagonists were given asylum and other rights enabling them to remain legally in Europe.

Please consult the websites below to understand the different profiles of migrants and immigrants:

I also invite you to watch the Le Monde (French newspaper) video on the subject, which is how I discovered what was happening thousands of miles from home:

I would like to thank Vincent Latour and Simon for their testimonials, and in particular Hind for her story. This brilliant and courageous young woman touched me (deeply), and I will be visiting her in Belgium.